We often see disparities or statistical trends where people of different genders, ethnicities, and abilities don’t have the same access to financial stability, decision making or health outcomes.

But these disparities didn’t just happen in a vacuum.

They are often the result of specific policies or widespread institutional practices that create these inequalities.

What are racial disparities?

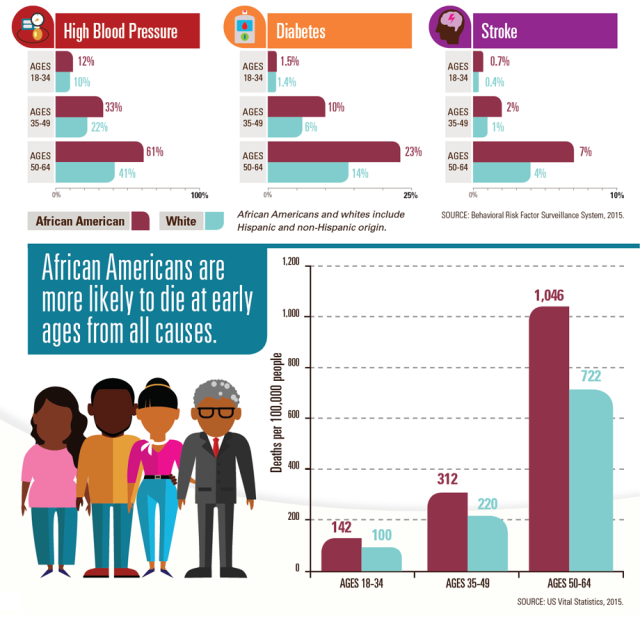

The term “health disparities” is often defined as “a difference in which disadvantaged social groups such as the poor, racial/ethnic minorities, women and other groups who have persistently experienced social disadvantage or discrimination systematically experience worse health or greater health risks than more advantaged social groups.”[2] When this term is applied to certain ethnic and racial social groups, it describes the increased presence and severity of certain diseases, poorer health outcomes, and greater difficulty in obtaining healthcare services for these races and ethnicities. When systemic barriers to good health are avoidable yet still remain, they are often referred to as “health inequities.”[3]

Why Bring Up Racial disparities?

In the United States, like many industrialized nations shares a history in which European colonists immigrated and seized property from indigenous populations in order to generate wealth for European property owners but restricted wealth building opportunities for people of other ethnicities with policies and practices designed to limit competition from other populations.

More importantly, these policies and practices were structured in such a way that prohibited non-white Europeans from making decisions about their own health, civil liberties, or living conditions. The policies also provided white property owners and post war veterans a financial and educational wealth-building advantage during the same period these policies were enacted to create disparities. Any advances or successful efforts to shift policy to create a more equal society in which everyone has the opportunity to build free and healthy lives has been undermined by those who have benefitted from these disparities through policies like (redlining, urban renewal, Nixon’s deregulation and shift toward a debt based monetary system, mass incarceration, gentrification, etc).

The choices made by these policy makers throughout United States history have created stark differences in wealth and health outcomes.

In 2016, the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) and the Corporation For Economic Development (CFED) released the findings of a study in which they investigated trends in household wealth over a 30-year period and found that without ‘significant policy interventions, or a seismic change in the American economy,’

If current economic trends continue, the average black household will need 228 years to accumulate as much wealth as their white counterparts hold today. For the average Latino family, it will take 84 years.

The research showed that the average wealth of white households increased by 84 percent between 1983 to 2013, which was three times the gains that African-American families saw and 1.2 times the rate of growth for Latino families.

Coincidently, significant disparities in health resulting from disparities in access to care resulted in a similar trend among census tracts that experienced these wealth disparities.

While faulty cultural narratives that attempted to pathologize (or stereotype and stigmatize) communities of color for these outcomes, the realities these communities face was much more a byproduct of this long history of political and social apartheid than could be attributed to individual behaviors.

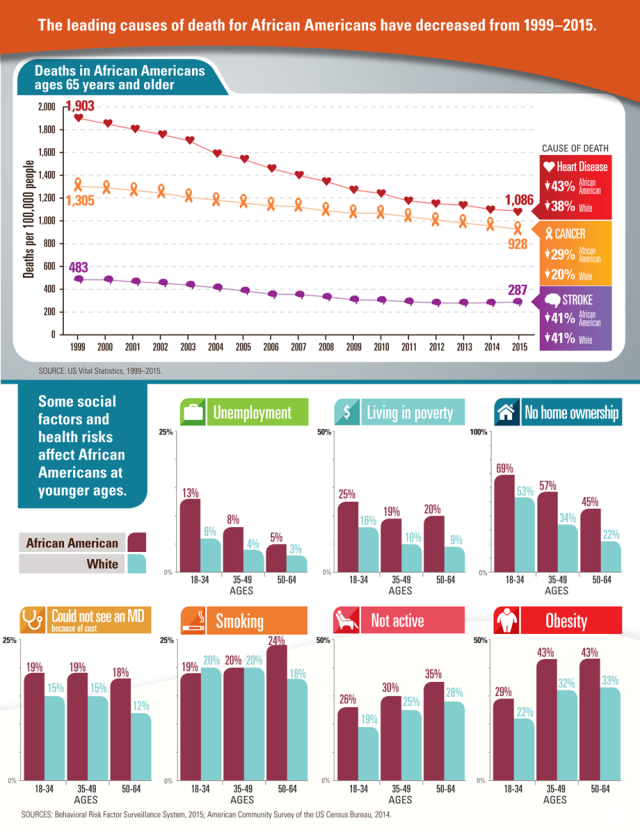

While factors like poverty, unemployment, and unhealthy health behaviors were assumed to be the product of poor moral or cognitive capacity to make better decisions, public health researchers began to use epidemiological surveillance methods to investigate the root causes for these health disparities.

What they found was that many of the communities that faced these health disparities were concentrated in census tracts with low homeownership and limited access to resources due to how cities were zoned and disparities in hiring and lending practices.

Residents in these census tracts who experienced higher rates of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes were significantly less likely (statistically) to have access to safe affordable food, were more likely to live in contaminated housing or to experience violence in their neighborhoods (by both law enforcement and from vigilante groups who took retaliation into their own hands rather than risk being placed into a victim/offender relationship with law enforcement), and were also less likely to earn the revenue or secure loans to get their basic needs met, let alone for high ticket costs like healthy housing, transportation, or childcare.

Whereas previous generations of black and brown immigrant families were able to pool resources and use tools like public housing and food assistance programs that were initially designed to help white working class workers save up enough money to purchase homes with government subsidies, which was the origin of much post-war middle class wealth.

Deregulation policies which ended the savings and loan model and government subsidies initiated by Nixon changed the monetary system in which wealth was transferred and how that distribution was concentrated. Families who could access to loans were expected to borrow loans and pay installments over long periods of time in order to create wealth using interest payments and stock dividends for the property owners and regulators who already had access to homeowner equity and other forms of pre-existing wealth.

Nixon’s War on Drugs criminalized black and brown communities for narcotics consumption and distribution, even though the primary source of drugs entering the country came through the military and medical system. The mass incarceration of black and brown communities created additional barriers to social mobility resulting in hiring and voting restrictions.

But the historic disparities didn’t just harm the black and brown folks who consumed controlled substances. The effects of these regulations and practices also replicated disparities among members of these communities who did their best to assimilate into a monetary system that wasn’t designed to include them.

In 2018, the research team led by Dr. Willian Darrity and Darrick Hamilton that investigated whether African Americans who:

- invested in higher educational attainment

- invested in homeownership

- purchased and banked from an investment pool concentrated predominantly within the black community

- put more money into savings

- increased their financial literacy

- developed better entrepreneurship skills

- emulated successful minorities (e.g. entertainers, athletes, investors)

- improved soft skills or ‘personal responsibility’

- created stable two parent families

would be able to close the wealth gap in their Racial Wealth Gap Study.

What their study did was debunk many myths and narratives that had been used to discredit the efforts of communities that had experienced racial and financial apartheid

So how do we repair it?

Click to learn more about the role of Equity in ending racial disparities.

Pingback: What is Equity?