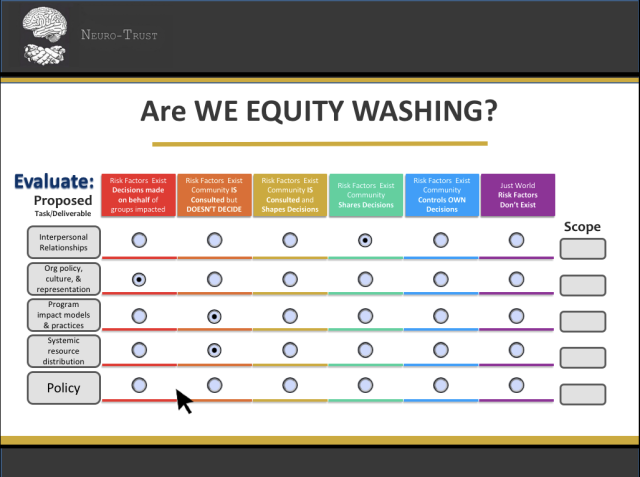

By request, I will be developing content for a post about an assessment rubric I wrote on ‘Equity Washing.’

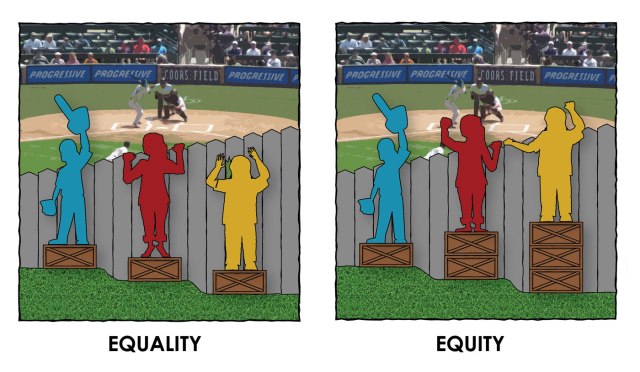

In order to understand what equity. washing is, we first need to define what Equity IS and ISN’T.

What is Equity?

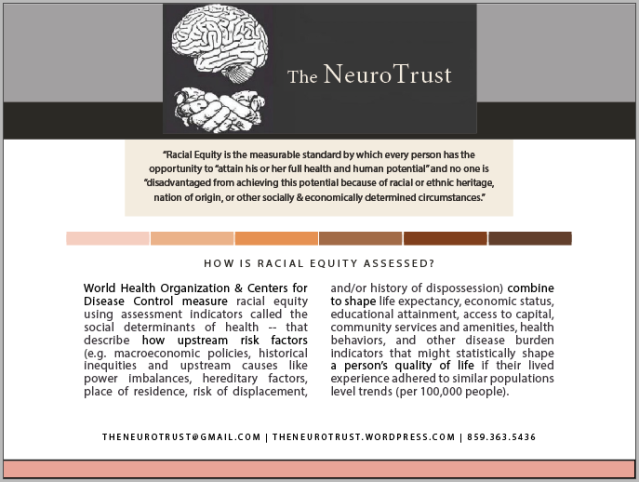

In the field of public health,

“Health Equity is the measurable standard by which every person has the opportunity to “attain his or her full health potential” and no one is “disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or other socially and economically determined circumstances.”

— C E N T E R S F O R D I S E A S E CO N T R O L

The World Health Organization and Centers for Disease Control measure health equity using sets of risk factors that describe how upstream risk factors: (e.g.

- macroeconomic policies

- historical roots of inequities

- systemic power imbalances, and

combine with:

- hereditary or developmental factors

- economic status, educational attainment

- place of residence (urban/rural), subnational region, and health behaviors)

to shape life expectancy, mortality, and other disease burden indicators that might statistically shape a person’s quality of life throughout their life course.

This means that if a person’s life experiences followed the same trends we see statistically at populations level (or trends we see that cluster in units of 100,000 people across many communities) that reflect the trends we see in people who shared their hereditary and economic circumstances, the person would be statistically more likely to have health outcomes consistent with the regional trend unless a policy or institutional intervention changes their life course.

We often see disparities or statistical trends where people of different genders, ethnicities, and abilities don’t have the same access to financial stability, decision making or health outcomes.

But these disparities didn’t just happen in a vacuum.

They are often the result of specific policies or widespread institutional practices that create these inequalities.

For example, in:

Racial disparities

In the United States, like many industrialized nations shares a history in which European colonists immigrated and seized property from indigenous populations in order to generate wealth for European property owners but restricted wealth building opportunities for people of other ethnicities with policies and practices designed to limit competition from other populations.

[If you haven’t already, be sure to check out my post ‘How Racial Disparities shape Health Disparities‘]

Gender disparities

In the United States, like many industrialized nations shares a history in which women were prohibited from owning or managing property or asset related decisions without permission of their parents or husbands. The United States also shares a history of violence against gender nonconforming communities that often results in discrimination and exposure to violence.

[Stay Tuned for my upcoming post about how Gender Disparities shape Health Disparities]

Disability disparities

In the United States, like many industrialized nations shares a history in which people with cognitive and developmental impairments were prohibited from making decisions about their own access to healthcare or living conditions.

[Stay Tuned for my upcoming post about how Ablelism shapes Health Disparities]

What is the role of Equity in repairing health and economic disparities?

These policy level, economic, and epidemiological studies, used populations level evidence and an empirical, peer reviewed methodologies to demonstrate how this history of apartheid, and the people who benefit from the disparities formed by these policies and practices have a direct responsibility to repair the harm they have and will cause to many generations to come.

While many of our policy and philanthropic models used to provide assistance to vulnerable populations are built upon outdated narratives that attribute these disparities to ‘a lack of will’ or ‘moral failure’ rather than acknowledge and dismantle the structural disparities.

The principles of equity call upon communities to share ownership and investment in the repair of this deep, systemic structural harm prioritizing the needs of those most in need or crisis so that they have access to the resources they need to build resilience (in a way that’s trauma informed and community led).

Consequently, many policy makers and philanthropic funders who express a desire (often in the form of a spoken or written commitment) to invest in this structural repair either have little knowledge of this history and use a ‘deserving poor’ approach to investment, or take so much ownership of dictating how repair should happen that they end up replicating many of the systemic harms and practices that harmed these communities and exclude communities that have been harmed from the decision-making process. This is more often than not predicated on the basis that these gatekeepers:

- aren’t aware how they replicate supremacist power dynamics

- pathologize these communities and don’t trust these communities to advocate for themselves

- see criticism from these communities as something to be defensive or resentful about rather than an opportunity to collaborate or support those who are closest to these challenges

So how do we repair it?

Stay tuned for more information addressing many of the strategies we can use to share ownership and investment in repairing these systemic harms.